By Emma Baigey

Featured Photograph by Josip Artukovic

Simon Roberts is a widely exhibited visual artist with a host of accolades and critically acclaimed monographs under his belt. His tableaux photographs of the British landscape interrogate culture and its relationship with history, public space, and identity. His work expands across photography, video, text, and installations and always carries a message, either implicitly or overtly, and often one about the cracks in modern society.

We caught up with Simon Roberts to talk about the inspiration behind his work, adapting creatively to covid restrictions, and what he’s working on next.

You’re most well-known for your tableaux photographs of the British landscape. What inspired this characteristic style and how did it initially emerge?

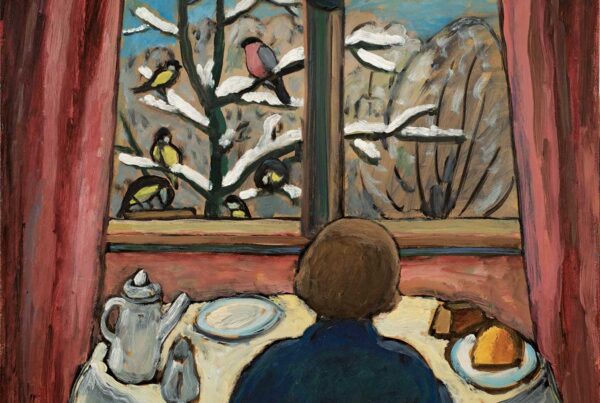

I guess it initially emerged as a way of finding my own way of exploring the British landscape. I wasn’t doing anything new in terms of going out to explore one’s homeland, in that, a lot of photographers have done that over the course of time, so I needed to find a way to add something to that pantheon of work. When I was making work in Russia, one of the things I found interesting was exploring the vastness of a landscape and how people sit within that space, so I began these photographs of small figures within the landscape. It was visually inspired by Dutch and Flemish winter landscape painters like Bruegel and that sense of creating narratives within a landscape. When you look at these paintings of naturalistic backdrops you have a range of narratives taking place within them, from buildings, how people are interacting with one another, and the different stories taking place between these people. I thought it was an interesting way to look at how we use the landscape ourselves and how we gather in space. To do that I needed to find a way of composing the picture that gave you this sense of landscape not as a passive thing, but as something that we used and interacted with. Having some elevation gives you perspective and you get a much better sense of that conversation. It also plays on historical paintings we see in the National Gallery like William Powell Frith ‘The Derby Day’, this idea of creating moments in time that are capturing a slice of life. Whilst these painters used a lot of artistic license in bringing different characters together in one piece, they were also inspired by photographs taken at these scenes. To some extent, I see that in the same way here. I’m trying to find a moment in time we can really dig into.

Equestrian Jumping Individual, Greenwich Park, London, 8 August 2012 from the series Merrie Albion

© 2023 Simon Roberts

Your earlier monographs like ‘Pierdom’ and ‘Green Lungs of the City’ capture our attachment to structures and public space and the evolving role they play in the community, those specifically focusing on piers and urban parks. How do you decide on these subject matters?

Each project is thematic, so ‘We English’ was very much about looking at leisure in the landscape, what we do in our pastimes and how we use the landscape as a backdrop. ‘The Election Project’ was a commission that became part of ‘Merrie Albion’, which was a book I did about politics. Then I was thinking about other themes like immigration, devolution, or the economic crisis and austerity. Each of those became themes that I could explore within a setting, whether that be urban or rural. ‘Pierdom’ was about looking at the coastline of Britain in a unique way, given that piers to some extent tell a story about changes in the British coastline, from the early Victorian industrialists building these structures to the post-war boom to a period in the 60s where the British coastline saw a decline as we all traveled abroad. Now there’s this slow reawakening with staycationing, and there you’ve got links to climate change and the cost of living crisis and people not being able to afford traveling as much. It was a way of thinking about this through architecture, as the piers are these eccentric, weird structures that are particularly British.

‘Green Lungs of the City’ was not really about Britain but was about the idea of an urban park and how it’s been used throughout history as a way of offering the public a place of refuge in the city. It was also about how that’s becoming more important in terms of how we think about urban planning going forward, and the health and environmental benefits of green spaces in a metropolis.

It’s interesting that you’ve just described how some of your work is political in a more reflective way. Other works of yours, such as ‘Between the Acts’ and ‘This Is a Sign’, seem to be more overtly political. What drives this difference in approach?

With the landscape pictures, I’m giving the viewer more of an opportunity to take a stance. I’m being more objective in the way I create those pictures. I’m democratizing the scene and keeping as much of the landscape in that’s of interest. With more targeted works I’m taking more of a political position, whether that be about the awful effects of austerity or how the pandemic affected us. So I think it depends on the subject and how angry I’m feeling at the moment in time.

Your themes have recently become more introspective, which is evident through ‘The Weeds in the Wilderness’ and ‘The Celestials’. Is this reflective of a change in personal style or wider culture, or both?

A mixture of both. When I published ‘Merrie Albion’ in 2017, I saw it as a mark in the sand. I’d been making a particular style of photography for 10-15 years and I wanted to begin experimenting with other forms of making work. ‘The Weeds in the Wilderness’ was partly a reaction to that, partly to see whether I could make photographs without people, but partly also a reaction to Brexit and the frustration I felt about it. It was an opportunity to disappear into the woods, but of course at the same time still trying to think about what it is I wanted to say with this work. It still had a message – one about, again, urban development and how we’re losing a number of these ancient forests and woodlands. So with all the work, there is a message there. It’s not all introspective in the sense that… I’m not navel-gazing. I’m still trying to communicate an idea, but it’s motivated in the background by different states of mind.

Something like ‘The Celestials’ and ‘Beneath the Pilgrim Moon’ were stylistically very different, and were born of an inability to make work in the way that I had normally because I couldn’t travel or move. I wanted to embrace those restrictions and see how I could react creatively. As a visual artist, I’m always trying to push myself in terms of how I make work and find new solutions to problems. That’s what it was; part frustration, part excitement, part experimentation… which doesn’t always work. But I feel in those two situations it did. There are plenty of things I do that don’t work (laughs), so it’s always nice when something does capture a moment. Like ‘A Daily Sea’ which started during the pandemic. This was just me taking a photograph of the sea every day as a way of clearing my head and feeling like I wasn’t moving backward, but then when I started sharing them online people started really interacting with them. It wasn’t something that I set out to do, but it became a process, almost like a daily meditation, and then it turned into something bigger. It’s always interesting when a body of work takes its own path, and it’s partly led by other people.

As an artist interested in communal experiences and collective identity, how has the pandemic impacted your photography?

It’s enabled me to experiment more and to think more widely about how I want to make work going forwards. I’m less restricted by boundaries, which are either put on by myself or by industry. There is this sense that you get pigeon-holed over a period of time into making a certain kind of work, and there’s no doubt that I felt that to some extent and was taking on commissions where I was being asked to make a certain type of ‘Simon Roberts’ picture. This has enabled me to move on from that and to put work out into the world that people don’t necessarily recognize as mine, but that has become owned by me in the sense that the work’s been exhibited and published. Now, I feel freer in terms of where I go next, which is a nice position to be in.

Shrouded Sculpture #1 (Theseus and the Minotaur by Antonio Canova), 2021 from the series Beneath The Pilgrim Moon © Simon Roberts

Your recent exhibition ‘Beneath the Pilgrim Moon’ is quite different from your earlier work. In which ways did covid inspire this change and the photographs themselves?

Photography for me has always been a tool for expressing an idea. The key is to find out how to use the camera to express that idea. A lot of people know me for the colored, tableaux pictures, but prior to that I was doing portraiture, I was using square-format black and white… I’ve used a whole range of cameras and tools to express an idea, for example ‘The Credit Crunch Lexicon’ was all made from text. It has loosened the attachment I had to one form of image-making and hopefully opened up a new direction where I can make work that is more multi-disciplinary. I like the idea of collaboration with other artists, which is not something I’ve done much of. Although a lot of the books I’ve done have been a collaboration between me and the designers and publishers, that’s always a rewarding experience to be part of a group of people that bring something to fruition.

You mentioned new things being revealed through the covering of the statues in ‘Beneath the Pilgrim Moon’. What were these discoveries? How did you spotlight these through your photography?

Whenever we look at something, our eyes are drawn to particular things that the artist wanted us to see in a sculpture. Then, when you drape something in plastic and light it in a different way, suddenly you’re drawn to new aspects of the object which were maybe before deemed somewhat banal or secondary to the main message. Any kind of finger or piece of marble skin touching the plastic suddenly comes to the fore. It almost looked like fabric, this moment of pause where something was being held back, and then suddenly you get this feeling that they’ll be revealed again. I liked the expression that they were giving off, and also the way that you see them in space. Usually, when you walk through a gallery, there tend to be a lot of people. There are a lot of other visuals around the space, and what I’ve tried to do is isolate these figures in a relatively darkened environment. Your eyes aren’t given any opportunity to see anything else. You’re presented with what I’m trying to show you, at the same time revealing elements that to some extent are challenging to the eye. There’s one particular picture where you almost want to go up and rip this thing off. It’s quite emotive in the sense of how we think about covid, and how it was a barrier to so many of us. I like the fact that when you look at these pictures, there’s a sense that you want to rip them open and reveal something new and be reborn. Or maybe that’s me overhanging my photographs (laughs).

To channel that question into your entire career… Aesthetica magazine wrote that your photography reveals ‘truths hidden in the collective consciousness’. What are some of the key truths your photography has revealed to yourself throughout your career?

Is there truth in a photograph? That’s the big question. What I’m trying to show is my truth. It might be different from other people, but it’s how I respond to a place. Part of the reason that I’m a photographer is that I want to go out into the world, I want to experience the landscape, I want to witness a moment in history, I want to feel a moment in time. The trick is how you do that in a still image and how you can translate that moment into an experience for another viewer. The least I can do, and how I would deem something successful, is if someone responds to that in a similar way to how I responded to that landscape in the physical experience so that the work embodies not just an individual but a collective sense of time.

Where can people see your work on the web and in person next?

I’m about to publish a new book called ‘Cathedrals Are Built in the Future’ which is a series of photographs made prior to the pandemic in Cuba over a couple of years. They’re going to be published by Another Place Press at the end of this month. I’ve currently got some work in a show in Pallent House Gallery in Chichester looking at the Sussex landscape, which is a beautiful exhibition based on looking at artists who have responded to Sussex, from Turner and Constable to Paul Nash and more contemporary artists like Tom Hunter and others.

NOTES

Several of Simon's works are included in the group exhibition Sussex Landscape: Chalk, Wood, Water at Pallant House Gallery (Chichester), which celebrates Sussex as a place of inspiration for artists from J.M.W Turner to Vanessa Bell.

His most recent book, Cathedrals Are Built in the Future, featuring photographs from Cuba, has just been published by Another Place Press (Nov 2022)